This year, I finally finished playing through the first Psychonauts game. I have been attempting to imagine what it would have been like to play it when it was first released in 2005, at a really difficult period of my life, and before I had given trauma and depression any serious thought. Had it provided me with any insightful information? I’m not sure. Although Psychonauts is a creative and compassionate game, it is by no means a clinical or cohesive examination of mental health, nor does it make any claims to be. The game is a psychedelic 3D platformer that reworks clichés of lunacy and repression in a humorous and humanizing way. Players may explore mental settings ranging from Oedipal circuses of pulsating flesh to Manchurian Candidate suburbia. It’s far more of a bizarre gothic comedy than an instructional story, with its winding asylums and tangible emotional baggage. However, I believe that the 2005 version of myself may have found comfort in its instructors, Sasha Nein, Milla Vodello, and yes, even Coach Oleander, who openly shares their all-too-fragile inner lives with you in order to help you refine your abilities as a burgeoning psychic agent.

While I rolled and bounced around those brilliant stages, fiddling with Sasha’s tightly wound neural plumbing and paying a visit to the house fire inside Milla’s cerebral disco, I reflected on how, in different ways, my own teachers had shared their knowledge with me, put up with my intrusive questions, and generally exposed themselves so that I could grow. I don’t want to imply that limits have no role in education or that this is how everyone teaches or is educated. However, it’s undoubtedly the type of relationship that many educators and game creators want to establish: this is the universe of my experience. Come spend some time with me and see what insights you may uncover. After gaining knowledge from these realms, you may assist its owner face their inner demons and uncover long-forgotten truths by restoring them. Psychonauts 2, which is the same smart and compassionate game as its predecessor but sleeker, busier, and with updated ideas on mental health that reflect, among other things, the pressure and burnout of the original’s development, continues this premise.

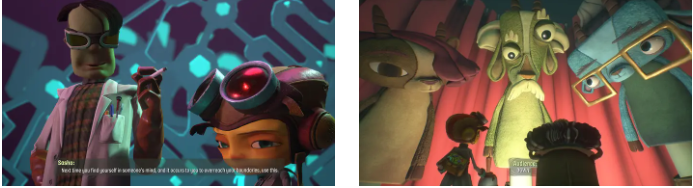

Razputin Aquato, a former circus performer who is now a mind-diver, joins the intern program at Psychonauts HQ, an Epcot Center-style hub where you can discover brains in hamster balls and a guy disturbed by images of flying bacon. Psychonauts 2 picks up immediately after the events of VR expandalone Rhombus of Ruin. The first thing you do is break into the memory of a guy from the previous game named Dr. Loboto. He is connected to a renowned psychic megavillain from many years ago. The story revolves on examining the megavillain in question—who, surprise!, could be more than just a memory—and her connection to the original Psychonauts, a group of traumatized hippie Avengers whose brainscapes all desperately need a janitor visit.

The Motherlobe, together with the surrounding woodlands, mine tunnels, and swamps, are the intricate and dramatic landscape of the game. It has a plethora of items, bounce pads, rope swings, rails, ladders, collapsing platforms, and supplementary fetchquests. The “dungeons” are the thoughts of the individuals you encounter; to extract information about your ultimate enemy, you must delve into and revitalize their brains. From the first game, Milla, Sasha, Oleander, Ford Crueller, and Raz’s intermittent lover Lili are back; newcomers include a group of bullies who harass other interns and Raz’s circus siblings, who were all brought up to distrust psychics and are hence wary of their errant brother. There are some amazing sketches, such as the intern making pancakes with the help of some frightened forest creatures (“I CAN HEAR YOU ROLLING YOUR EYES, MRS THATCHER”), splitscreen heist sequences, and any scene involving Raz’s sugary-savage mother Donatella. The writing is more sweet and dry than laugh-out-loud funny.

Raz is much the same lanky but clever 10-year-old as before: the brunt of many jokes, endearingly innocent at times, wise beyond his years at others. Although the platforming controls have been improved, he still possesses all of his previous psychic abilities, including telekinesis, mind bullets, pyrokinesis, the ability to turn other characters into CCTV cameras through clairvoyance, and the capacity to channel his brainwaves into a balloon that can be dangled to glide or run on for speed. He is also still a skilled acrobat.

Complete with warts, the previous advancement system is also returned. Psy-cards are inserted into eyes to enhance skills, which come in groups of four and earn points for your intern card. It’s still a rather devious method of leveling up, reminiscent of Destiny’s absurd currencies, and that’s just the beginning. Psychonauts 2 features a whole maze of fallen stuff, including “half-a-minds” that may be coupled to raise your maximum health, “insight” statuettes that provide you extra level-up points, and psitanium shards that you can use to purchase consumables and “pins” that change your skills. But it does so with grace, as the majority of the collectibles either make a joke or enhance the scene in some way. Examples include a sentimental piece of luggage that beams when it is reunited with its matching luggage tag and the use of “figments of the imagination” to add depth to levels with doodles that are thematically related to germs, tombstones, and cats.

At moments, Psychonauts 2 seems to be trying too hard to be a fighting style builder in the vein of Devil May Cry. Extra combo hits, ground pounds, health draining, dodge attacks, and projectile modifications are among the upgrade choices. Even with the addition of a new auto-lock, the main combat isn’t particularly engaging or tight enough to warrant all the other features, and in any event, 3D platformers like this one work best when your powers are clear and undistorted. It’s a hassle to continuously opening the ability wheel to alter things up during multiple-wave confrontations, and the techniques are seldom more difficult than hitting an adversary with the appropriate talent.

But it’s more than made up for by the mindscapes. Psychonauts 2 is exciting in part because it’s a return to the idea of level-based worlds, which are becoming rare in the industry due to a disdain for any kind of interruption. This is partly due to virtuoso “no-cuts” auteurism and partly to the contemporary cult of engagement and monetisation. Double Fine avoids all of that without trying because it chooses mental geography above physical geography. Naturally, there are pauses in the flow—after all, who among us really thinks in a single universe all the time?—and our brains are not all the same size.

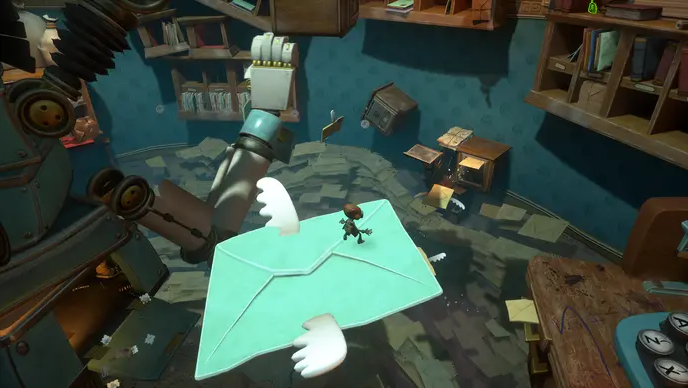

Psychonauts 2 is like unwrapping a bunch of gifts when you play it. While there are traces of classic platforming elements like lava and ice, the majority of the levels are exciting creative creations that subtly alter the core mechanics of hopping and shooting. There’s a full-fledged 90s cooking show within one brain, complete with some of the most well-observed musical pastiches I’ve seen in a game, with terrifying hand puppet judges and an enthusiastic audience of meat and vegetables who have to prepare in the allotted time. A “Feelmobile” transports you between the main stage and camping areas, while another has a rock concert dressed in Sergeant Pepper colors, with rainbow bridges snaking from prisms across a dazzling lake of stars.

These spaces all conceal other areas. Massive bottles on the tropical coast of a potted planet reminiscent of Mario Galaxy open like doors to an iridescent swamp of yellows and violets, with handy holes blasted out of the dirt by spouting seedpod heads. Another city level is situated in a very filthy bowling shoe, where germs in trilbies are waiting for the much-feared Spray-pocalypse to arrive. Though not nearly as inventive as the original game’s take on tabletop wargaming, there are references to other games such as Super Monkey Ball. Additionally, bosses, which were introduced as a result of Double Fine’s mid-development cooperation with Microsoft, are very elaborate in concept but executed a little shakily.

These universes transcend mere parodies. Psychonauts 2 may stray from tradition and allusions, yet its little details are meaningful. It all comes down to consistency and follow-through: if you’re going to recreate a character’s backstory as a theme park ride, you’ll need ticket booths manned by enchanted employees, gantries above that serve as observation platforms for stenciled handymen holding cigarettes, and a control room where Lili can issue directives into a microphone. With NPCs pursuing their own little stories in the corners, each inner world has a slice-of-life atmosphere reminiscent of Pixar. Examples include animatronic clerks becoming agitated over misdirected mail, a dragon attempting to talk down a knight in shining armor, and circus fleas squabbling over who gets to ride the trapeze first.

For the original game, everything of this was accurate. However, Psychonauts 2 distinguishes itself by carefully balancing a more nuanced grasp of issues like anxiety, addiction, and post-traumatic stress disorder with a caricature and empathy that treats brain anomalies as peculiarities. Although the game’s initial screen cautions you that it is a work of imagination, a feeling of duty based on collaboration with organizations like Take This nonetheless shapes the game’s levels and content. Raz, for instance, often requests consent before entering someone’s head, but it’s clear that this isn’t always feasible when bad guys are involved.

Recognizing that an action-platformer template may not be the ideal setting for what are effectively acts of intrusive therapy—or, in the case of hostile characters, sanitized interrogations—is a part of that responsibility ethic. This is particularly evident in certain new foes and gadgets. A grappling that is described as creating “mental connections” by connecting ideas with dotted lines between spirals of gray thinking is one of the new features. As soon as Raz gets his hands on this, he uses it to ruinously manipulate someone’s thoughts, turning their inner world into a tormented cross between a casino and a hospital. It’s a startling but welcome admission that using someone’s mental health as a test subject has the potential to lead to abuse.

Meanwhile, the enlarged roster of enemies teeters intriguingly close to a replication of crippling mental abnormalities in the vein of Serious Games. On the lighter end of the spectrum, there are Judges wielding enormous gavels; Doubts that weigh you down; and Bad Moods that float about cursing until you use Clairvoyance to peer through their eyes and locate the imprisoned heart that will make them laugh again. However, there are also more intense recreations of panic attacks, which take the form of multicolored monsters that teleport and spew darts until they get ensnared in a slow-motion bubble. When you first come across these beings, it’s inside the head of someone who is experiencing dissociation and sensory overload. Conversely, enablers are the goblin cheerleaders who provide invincibility to other cognitive fauna.

Psychonauts 2 is similar like unwrapping a bag of gifts when you play it.

There’s a conflict between Double Fine’s ongoing homage to different gothic clichés and the second game’s more serious knowledge of subjects like consent and gaslighting, but I never felt that Psychonauts took any harmful liberties with these depictions. A moment of awkwardness occurs when Agent Nein pulls Raz aside to give him a lesson about the previously mentioned act of wanton rewiring, all the while giving him the power to return to any brain he has visited in order to take care of any “unfinished business”. In this case, the platform game’s collect-a-thon feature triumphs over the narrative it aims to convey. The last level seems to follow this similar pattern, hinting at the rising self-knowledge and accepting ethic that permeates most of the earlier stages. However, it concludes with you punting someone’s excessively spiteful streak into a deep well of repression—because every platformer has a boss.

Though I’m not convinced these are all critiques. Part of the fun, in my opinion, is in seeing Double Fine navigate this intricate web of clichés and understanding, inadequately translating very complicated processes into buildings, adversaries, and powers. Once again, Psychonauts 2 is a world of flawed educators and learning settings, a place to process dark ideas with differing degrees of sincerity and ridiculousness. Its people are delightful to be around, and its environments are marvels of unmatched inventiveness. Even if I may have missed it the first time, I’m happy that indie games like this are still being produced.