Though thoughtful and ambitious, Amplitude’s major move for the historical grand strategy crown lacks a little something special.

Large-scale 4X strategy games have always included ideology. It is present in a very explicit manner, such as when you adjust the “authoritarianism” setting on the ideology screen of your empire. Additionally, there is ideology—that is, the developer’s ideology—behind all of that, which they may not even be aware of—that explains why they chose an authoritarianism dial in the first place and why it functions the way it does.

I’ll move on because if you use the word “ideology” too often, you’ll sound like Slavoj Žižek stuck on repeat. The idea is that in Humankind, the new historical grand strategy in the style of Civilization from Endless Legend and Space creator Amplitude, capital-I ideology is deftly handled in a manner akin to a consequential sliding scale system, while the developer’s little-I ideology is consistently felt. I’m informed that Amplitude has been wanting to create a game similar to this since its founding, and that their main motivation is to do things the correct way, whatever that may be. I adore it because of it, regardless of the result.

Aside from that, Humankind plays like the most thoughtful, philosophical, and historically true (if not exactly correct) game of its type. It sounds as if a bunch of very clever individuals got down in a room and carefully considered how to do things in the most realistic manner imaginable. This makes it, in many respects, the 4X game I’ve always desired—one whose systems function mostly in line with those of the real world and whose history is structurally linked with that of real humanity. The only issue is that after playing it, I’m not sure whether I still want it.

The current 4X, civilization, is by far the most similar to humanity in history. You can play Humankind right away if you’ve played Civ, particularly a contemporary one. In order to win the game, you must compete against other human or artificial intelligence (AI) civilizations by building cities on hexes, exploiting the earth’s natural resources, moving up the scientific tech tree, spreading your influence over religion or culture, creating and discovering wonders, and balancing the many socioeconomic pressures on society.

In reality, Humankind resembles a successor to Civilization in that it adheres to the same model, including the well-known rule of thirds: around two thirds of Humankind is unchanged Civil, but the remaining third, or two major aspects, have been reimagined. The victory condition is the first of those significant distinctions.

In the game Humankind, there’s only one way to win: renown. Fame is a numerical score that may be obtained by accomplishing several in-game objectives. At the conclusion of the game, the player with the highest score wins. The game ends for a variety of reasons: reaching a certain number of turns, defeating or subjugating every other player, finishing the tech tree, starting a Mars colony, gathering all the stars of the final era (more on that in a moment), or, somewhat surprisingly, making the entire planet uninhabitable for human habitation.

This is excellent, as is the case with most everything Humankind does. Amplitude’s first goal is to eliminate the “frustration” that arises when someone else wins against you by using a different win condition, such a cultural triumph, just as you were about to achieve your own scientific success. Second, it all boils down to wanting to retain as much historical accuracy as you can. The argument argues that even if many of the most well-known civilizations are no longer in existence, they are nonetheless well-known and, if not exactly respected, for the things they accomplished. This is how things operate in human history. If at the conclusion of the game no one else can equal the score you managed to obtain, you may still win the game even after you are eliminated.

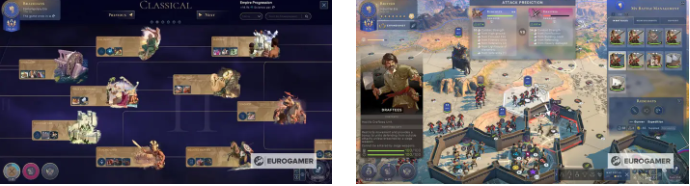

A system called “era stars” is in place to support this, which are essentially gold stars that you may acquire, much like a good little student. If you’d want, you can choose to be a student of absolutely brutalizing your foes in battle or using force to extend your area. With the exception of the very first era, each of the seven categories has three stars available for earning era stars, for a total of up to 21 stars per era (plus additional stars for accomplishing specific one-off tasks, such as being the first to discover a natural wonder or connect two cities by rail, and a unique “competitive spirit” star that establishes a sort of natural catch-up system to maintain balance). There is a significant and extremely ingenious catch to the basic rule that the more period stars you gather, the higher your score will be. Each era star awards you with a bundle of fame points.

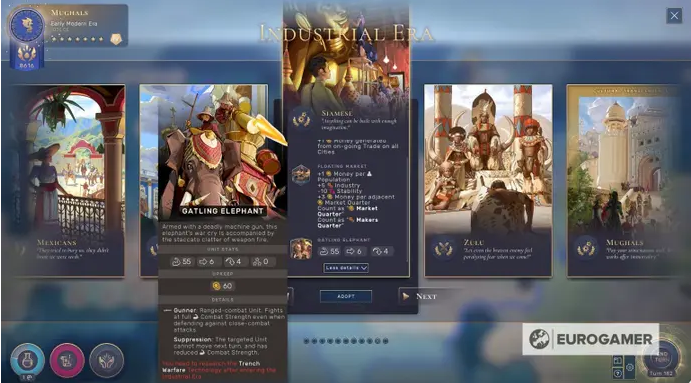

Stars in the same category as your existing culture are more famous, and here is where Humanity’s second major break from civilization, along with most other great plans, come in. Every player begins the game with the same blank slate—a solitary nomadic tribe that gradually expands as you explore—instead of selecting a specific civilization or leader like Genghis Khan or the Greeks. As you go into a new era, you choose your culture for that period. A specialty is added to the standard items such a special unit, passive ability, and building. Since the Mongols are known for their battle prowess, obtaining a combat era star—which is awarded for eliminating a certain number of enemy units—gets you more notoriety than other period stars, such as scientific ones.

Once again, it all boils down to authenticity—the idea of conducting humankind’s affairs in a manner that accurately depicts reality. In general, humans originated as tiny nomadic tribes rather than as separate civilizations like the Romans and the British Empire. Over time, people evolved, creating societies and cultures to fit the many conditions of existence. So it goes in Humankind, although quite cleverly on paper. Because you were rightly settled by some hostile independent tribes or an aggressive competitor culture, you may first prioritize your fighting skills. As a result, your first culture of choice may be combat-oriented, rewarding you with benefits and increased notoriety for successfully waging war. There are subtle differences even within that specialization; for example, some militarist cultures prioritize defensive above offensive capabilities and vice versa.

Then, in order to play at a higher level, you must consider how your choice of culture influences your notoriety more deliberately than by just responding to external events. If you were doing well militarily, for example, you could have been able to quickly produce soldiers by setting up a metropolis with several industrial districts, or makers quarters as they are called in humankind. Defeating nearby opponents prepares you rather well for a construction age, thus it might be wise to choose a “builder” culture next, which rewards you for doing nothing more than creating additional districts. And you may even plan ahead further, selecting a science specialist for the next builder period and profiting once more after constructing a ton of scientific districts (research quarters) to earn builder stars during your builder era.

A few astute trade-offs are also included in the scheme. Cultures are first-come, first-served, so you’re compelled to move quickly to the next one before you miss out. All you need is seven of the 21 available period stars in order to proceed to the next era. The longer you stay in one period, the more stars—and therefore, notoriety—you may accumulate overall. However, if you move on, you are unable to earn any stars from the preceding era. Another choice is to “transcend” your culture to the next one, which entails maintaining everything the same and losing out on any new structures or troops but gains you a 10% boost to all the notoriety you earn.

Thus, you have a more realistic beginning to the game, a more realistic system of civilizations for progressing through it, and a more realistic means of really winning—victory as fame or memorability. In principle, when you put it all together, you have a really intelligent system. On paper.

In reality, there are a few issues. Variety is one of the declared objectives of allowing you to travel across civilizations as you advance, in addition to realism. Since there are literally millions of options, it is theoretically impossible for two games to ever be identical. However, switching between specializations as needed causes the game to become somewhat hazy and rush you towards that soupy late-game state common to similar grand strategies, where you may have one or two strong specializations but actually need to be doing a little bit of everything to make them function, including money to support your troops, science to keep them advanced, industry to build them quickly, food to feed the populace, and so forth. Because of this, the everything-bagel state that characterizes the endgame in grand strategy games is by far their worst feature. Anything that makes the game seem more like that, rather than less, is problematic.

More than that, however, role-playing is a sometimes overlooked aspect of what really distinguishes a genuinely outstanding strategy game of any sort, particularly the larger ones. The whole purpose of the genre, whether it be Civ, Stellaris, or anything else, is really this: you play these games to pretend to be a shrewd technocrat, an omnipotent demi-god, or a blustering commander-in-chief, and it’s difficult to do when you’re only a technocrat for a few turns before the next era arrives. Before you can even take off the builder’s hardhat, you’ll be pulling a lab coat over one arm of your military fatigues and racing between roles like a one-man show. It is true that you have the option to remain a single culture throughout by using the transcendence option, but doing so will require a great deal of skill, particularly when facing militaristic opponents who have special fighter jets flying overhead or unique tanks rolling in. The idea is that you will need to adapt and change as you go.

The criteria for winning also influence that. I choose Genghis Khan, the Imperial Space Slugs, or any other character because I want to play for a military victory right away, making minor adjustments as needed. This kind of goal-clarity is what makes a game stand out from the others. In a sense, the objective is the astonishment that an opponent has beyond me to the position. When a good grand plan comes to a conclusion, things become tight. You’re trying to stave off an enemy army while rushing to build a spaceport or buying up artifacts to snatch some last-minute tourists away from someone who’s about to win a cultural war. Although you can theoretically use a variety of inter-player tools, such as influence-bombing a territory to make it yours or simply advancing through a city with your army to reduce the population of someone vying for an agrarian star, that’s less sophisticated than you’d hope for a game of this kind. The systems are largely quite insular due to the undymanic nature of era stars, which means once you get one you can’t lose it.

The historical 4X has a duty to arouse terror and amazement. Humanity often gives the impression that gratitude alone is sufficient.

Lastly, there’s a faint feeling that humanity is a little bit lifeless. The game itself is exquisitely designed, with a simple and mostly clear user interface (though there are a few awkward copy passages and the tutorial only explains that converting outposts can be used to build a city, which seems like a mistake but is understandable in the early stages of a launch). When compared to its contemporaries, there seems to be a noticeable lack of flare or celebration. There’s no fanfare at all when new technologies are unlocked; the music is fine but a touch unspectacular—no Baba Yetu or Creation and Beyond—and the narration is decent, if a little sardonic. These are games about mankind as a whole, about the marvels, the tragedies, the hopes, and the nightmares of human potential. Above all other games, the historical 4X has a responsibility to evoke dread and awe, and humanity often seems to believe that simple admiration is sufficient.

It’s quite unfortunate, considering how fantastic the product is overall. The little-I ideology system is a focal point; it is a set of left- and right-leaning axes that your civilization is pushed between based on the civics you practice and the choices you make about emergent narrative events. The more you go toward the extremes of an ideology, such as authoritarianism, the bigger the associated benefit and the worse the blow to your general stability, or the likelihood of uprisings in your cities. It’s logical! It makes a lot of sense, as so much of this game does, sifting between technical subtlety and astute social commentary—the epitome of the strategy game. Although religion is fairly basic and somewhat disconnected from other mechanics—you lose access to new tenets if you convert, and you may add new ones when you reach a new follower threshold—it works well. There’s no need to worry; diplomacy is basically functional, which is about as good as it gets in a computer game.

And it’s really fun in fight. Civ is beaten there by humanity, among many other things. It is similar to a scaled-down version of Age of Wonders, where a tactical fight analogous to XCOM is played out over many hexes of the battlefield while an overworld conflict is magnified. It has nice subtlety to it; sightlines and elevation are important, as is location and, at higher play levels, a clear knowledge of the capabilities of all the various units. It’s efficient, light, airy, and deep when desired. In many respects, it’s a game that captures a lot of the essence of Humankind: it may have a lighter touch than some others in the genre, but it’s also easier to get over the normal fog of a new strategy game and is elegant, well-thought-out, and clean.

The issue is that issues also occur while thinking things out. Though this may seem cliché, humanity appears to have evolved on its own ideological sliding scale. Authenticity on the one hand, and playfulness on the other. For now, Humanity is just a little bit too much to the later end of the axis, which leads to instability and the loss of the delicate balance that makes a great historical strategy sing. A little magic, the unpredictable quality of a Great Person, and the personal touch of recognized, well-known faction leaders are lacking from your standard, otherwise mannequin-like avatar. Alternatively, those vile, stereotyped adversaries that endure, rather than the identity of the person behind “the green faction,” whose moniker changes every few rounds.

Still. Since many games—especially ones that are based on open development like this one—inevitably alter throughout the months and years after debut, Amplitude has pledged to support Humankind for a while. The studio will still have a winner if they can find a way to balance things just a little more in the direction of enjoyment later on. Hopefully, an opportunity will present themselves that allows them to go that extra step.