I can’t get off Starfield. I constantly having my ass handed to me by pirates in space, and there are a million task symbols all over the screen. Luckily, the year is 2023. Grabbing my smartphone, I find myself staring at a page from Eurogamer’s fantastic guide to the Bethesda space epic in a matter of seconds. Ah, I see. After pressing that button, the only symbol visible is for my active assignment. Additionally, I must update my spacecraft. or get a superior one. These are the top ones, along with their prices and locations. Task completed.

Go back almost 40 years. Pentagram, the most recent isometric epic from Ultimate, stumps me. As usual with Ultimate, the instructions are elegant but not very helpful. I am aimlessly meandering around the two-color landscape, sometimes vaulting over blocks and dodging the occasional unpleasant. For its originator, Eurogamer is little more than a passing fancy, and anyhow, how would I get access to it? Though the idea of computer networking was starting to gain traction, it would take a while for common people like me to get access to the modern internet.

As a result, we made old-fashioned connections and shared advice on the playground. However, it wasn’t always effective, particularly in more difficult games like Pentagram. Only one path remained. Our network of Spectrum lovers, ready to interact with the experts and one another via our online and gaming publications.

How To Master Video Games, written by Tom Hirschfeld, was one of the earliest how-to books published in 1981. According to Julian “Jaz” Rignall, one of the first gaming advice writers in the UK, “I remember reading that and thinking, ‘holy shit, you can write about these video games and do tips for them.” “So when I came home from winning the arcade championship in 1983 and having this legitimacy of being a good player, I thought, well, I’ll start writing hints and tips.” At the time, Computer & Video gaming, or C&VG, was the leading gaming magazine in the UK. “The first thing I wrote was a guide to playing the Atari arcade game Pole Position,” Rignall says. “I developed this comprehensive tutorial after becoming an expert player of the game over the summer. It was basically instructions on how to drive around the course with some particular pointers; there was no template.”

As soon as the concept gained traction, Rignall started writing advice for Personal Computer Games, one of the first British publications to provide a regular tips section. By the time Newsfield launched its renowned Commodore 64 bible, ZZAP! 64, in the spring of 1985, the value of a consistent portion devoted to gamer assistance was well recognized. According to Rignall, “it was a very important part of the magazine.” “Market research showed that the tips were, along with reviews, the most popular parts of the magazine – but we had a gut feeling it was anyway, and it meant a lot of interaction with the readers.”

There were four to six pages of tricks, hints, cheats, and POKEs in every issue of ZZAP! 64, almost all of which were reader-submitted. The latter was crucial; it was a brief type-in program that granted the player limitless lives or some other kind of advantage. Rignall remembers, “The turnaround on POKEs was quick.” “Those guys had their routine, and I literally called them up and would ask for some POKEs for as soon as a game came out.”

The magazine would sometimes even give games to hackers in an attempt to publish the POKEs as soon as possible.

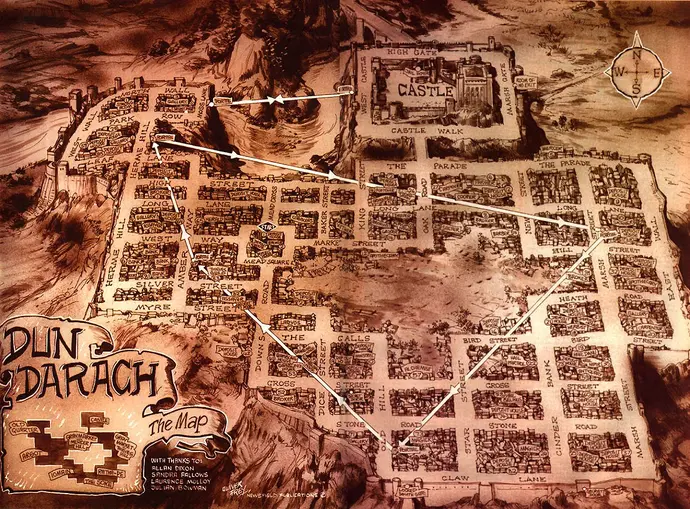

The early editions of Crash, the sibling publication of ZZAP! 64, had been noticeably tip-free. The editorial staff quickly realized this. Nick Roberts, who put up the advice section of Crash a few years later, says, “I remember as a reader, the big deal of the Atic Atac map.” “They ran a competition for readers, then Oli Frey turned these lined paper and pencil sketches into a map of beauty, with the prize of a cool ACG trophy!” Newsfield co-founder Oli Frey did more than just provide the covers and occasional comic strip and other graphic pieces; he also analyzed readers’ maps and turned them into works of art worthy of any wall. It was simple to get disoriented since many Spectrum games, like Atic Atac, stretched over hundreds of displays. We loved the maps, boy.

Of course, Newsfield wasn’t the only one to have a tip-related revelation. Your Sinclair, Crash’s competitor, realized early on that it required a tips area. Usually, the skillo YS chose to approach things a bit differently, having two distinct columns: Hack Free Zone for cheats and tips, and Hacking Away for POKEs. Former Your Sinclair staff writer Phil South explains, “I suspect it was because anyone can read a tip and try it, but inserting POKEs required a bit more savvy.” South, who wrote under the pen name Hex Loader, examined reader correspondence, reviewed entries, and typed everything into the two parts. “[It] was valuable to the readers, and the more of that we could do, the more value we would add to the magazine,” he says. “Plus, the research and testing of the tips was 80 percent done, and all I had to do was find out if they worked and write a few jokes in response.” Relentless mappers, like a young man called Mischa Welsh, even found themselves employed by the publication to provide material on a regular basis, and Your Sinclair went above and beyond the standard name-checks, publishing portraits and biographies of those who dared to submit suggestions.

As readers, we would devour all of these tricks, maps, and suggestions, meticulously enter the POKEs (which sometimes would even work), and then experience a revitalization with the corresponding game. This was one of two sections (along with the letters pages) that were more reader-created, although every other portion of the publications was thoughtfully crafted by its professional writers and freelancers. Roberts beams, “The process began with a giant postbag.” “We received hundreds of letters a month, and it was my job to sift through them and find some interesting ones for the Playing Tips pages.” Roberts wrote out each tip with a brief introduction and a name check for the contributing reader using a green-screen Amstrad PCW8256. “I created a rough layout outlining the locations of the pages in each issue after finding out how many I had. The POKE procedures were the mainstay of the advice pages, but we could utilize a decent map just as it was.” Roberts had to find the POKE’s game and practice the routine before meticulously penning it up for the magazine, just like all these tipsters. The first paragraph was the last component. Roberts’ Muses, Looking back, those Playing Tips pages read like a journal from my adolescent years; they discuss my nascent DJ career, my run-ins with the girls, and my holiday and Christmas activities. Very enjoyable to reflect about.”

Not everyone experiences things in the same way. “It wasn’t fun at all, as a journalist,” grimaces Rignall, who worked as tip master at ZZAP! 64 and Newsfield’s Amstrad publication, Amtix. “All you were doing was copy-pasting, copying people’s letters and looking at POKEs – it was incredibly tedious!” Another problem was timing: the magazine needed in-depth instructions for games that wouldn’t even be available when the reviews were published. Staff writers were unavoidably given that task. Rignall’s ideas are echoed by your Sinclair’s Phil South. “Aside from the tedious retyping of everything, it was a breeze. All I needed to do was think up some clever jokes. That really very much sums up my whole career as a journalist.” Your Sinclair eventually combined its two parts into one magnificent Tips spread: coworker Marcus Berkmann entered the realm of POKEs and pointers, while South moved on to other responsibilities. South chuckles, “He was a very meticulous cove, old Berkbilge.” “He had very tiny precise handwriting that looked like notes taken by miniature spiders.”

The tips sections, which people flocked to, caused conflicting feelings among the journalists who created them. Games got more sophisticated but less obscure as the 8-bit era faded. Long-form guides replaced the POKE, the ubiquitous Eighties magazine staple, as the latter gradually vanished from circulation. According to Rignall, “I think it peaked around 1994 and then just slowly faded at the end of the ‘nineties.” I believed Gamefaqs was amazing right away and would completely replace the need for magazine hints and advice. You could immediately get these really thorough written instructions, and people were doing them for free.”

Journalist Keith Pullin began working with PC Zone in the late 1990s, having gained experience as a “Games Counsellor” on Nintendo Hotline, an official service provided by Nintendo to provide advice and assistance with their games. Remarkably, one of his first responsibilities was penning a Dear Keith type advice piece, a.k.a. the “agony aunt.” “The weird thing was, it was mostly still letters, actual snail mail,” he informs me. “There was an art to finding the ones to publish and respond to, and the holy grail was finding a game that was reasonably popular and current, so people would be interested in it.” Like Crash’s adventure column in the 1980s, this was part of a wider tips section where readers would ask Pullin for a hint or tip, and he would answer. If he could, that is. “Quite often [the letters] just didn’t make sense,” he says with a chuckle. “The one piece of information that people tended to forget to mention was the name of the game!” Pullin also commandeered the instructions area, penning massive essays devoted to a single game. “To attempt to get hacks, level skips, game saves, or anything else to lessen the agony, you would get in touch with the publisher or developer. Next, you needed to get specific screenshots of the particular item you were discussing. I think that was some of the hardest labor I’ve ever done.” And that was just the hardest part of it. That involved reducing the whole text to 2,500 words. It implied that the objective of a level on a game like Carmageddon 2 would be reduced to “Kill everyone.” Leap across the chasm. Step into the mall. Murder each and every one. Get out of the shopping center. I’ve frequently questioned if anybody is really benefitted by this degree of ambiguity.”

Crucially, even though the advice sections continued to appear in publications like PC Zone, they were no longer seen as essential as they had been in years before. In 2001, Keith Pullin published his last Dear Keith; by then, he was mostly relying on the internet for his knowledge. That same year, his last PC Zone guide was published. Throughout the 2000s, cheat codes and manuals continued to appear in a variety of video gaming periodicals. There were even specific tips publications, like the venerable PowerStation. It was not to last, however. The internet had prevailed.

Though tips and guidance are readily available these days, these sections were formerly more beloved by us for reasons other than their suggestions. For editors like Julian Rignall, testing those POKEs and typing them all out may have been an excruciating task, but for us readers, the magazines’ interactive nature served as our portal to the world of the ZX Spectrum and Commodore 64. Nick Roberts remembers, “Magazines were always about being part of a club.” I believe that readers have been drawn to that club for a considerable amount of time. That has never truly been supplanted by the internet.”