The ongoing review of Avatar: Frontiers of Pandora showcases its stunning visuals and foreseeable storyline

Avatar: Frontiers of Pandora is still developing, but so far it’s been exactly what you would expect from a Ubisoft game: a vivid, beautiful environment sprawled over a standard formula.

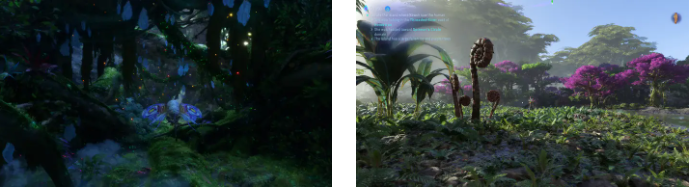

Remember that scene from The Wizard of Oz’s opening? When the farmhouse collapses, the twister stops spinning, and Dorothy opens the door to discover that magnificent, magical, and brilliant world? I experienced precisely that when I first entered Pandora.

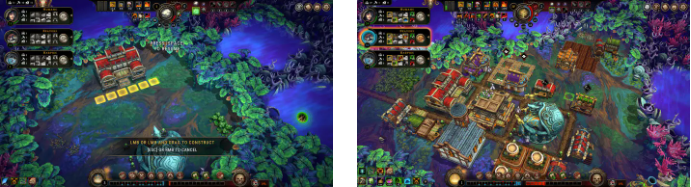

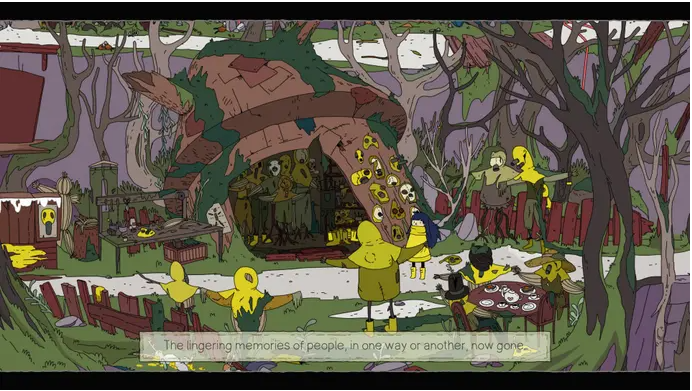

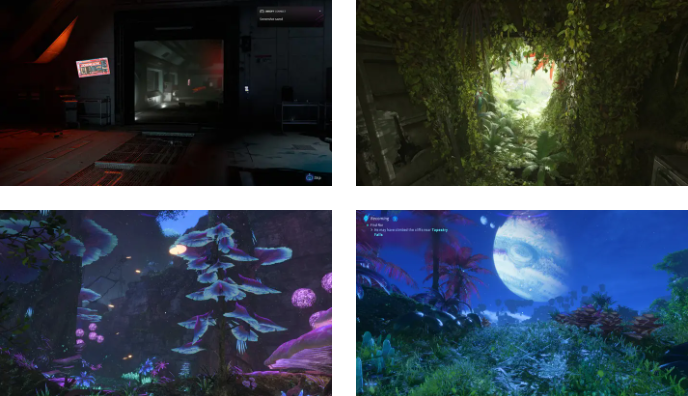

There, sunshine dapples through the canopy and showers gems of white light into the lakes, streams, and waterfalls below. It’s a joyful, magnificent, mesmerizing burst of color and texture. The fauna here is imaginative reimaginings of the creatures we know on Earth, so there are birds, fish, and deer, kind of. At first, there’s simply so much things, it kind of hurts your eyes. It causes some mild brain damage. Specifically, what should you be looking at here? The tree? The climbing vines on the tree? The vegetation encroaching onto the vines clinging to the trees? The shadows of deer munching the vegetation clinging to the vines clinging to the trees? Where do one life finish and another begin? Where should I go from here? What on earth am I meant to do?

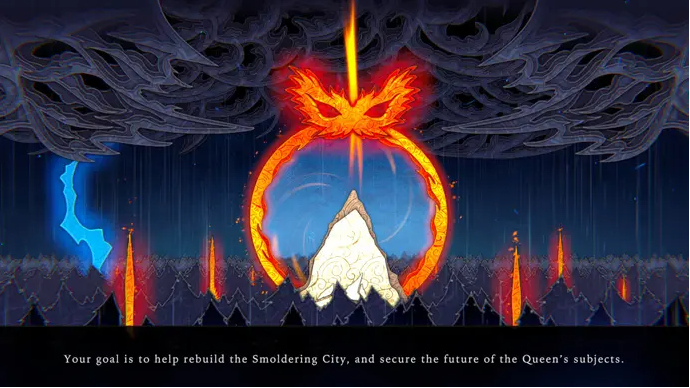

Avatar: Frontiers of Pandora even masterfully executes the cunning bait and switch from The Wizard of Oz. You spend the first half of your voyage stuck in the drab, dying gray world of humanity—a chilly environment made of steel, concrete, and fluorescent lights. This place lacks color. No light. Not a chance. You’ll enter Pandora only after scuttling through shadowy ducts, thrusting yourself headfirst from a life of dull monotony into an odd, exhilarating new technicolor world that you and the Sarentu you embody must explore together.

Frontiers of Pandora can be understood without prior knowledge of any Avatar material, and I can say that with confidence since I haven’t seen the movies or even heard anything about the series. That being said, it makes little difference; these analogies aren’t clever or nuanced.

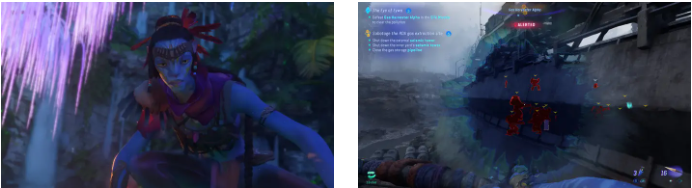

The parts of Pandora where humanity has staked its claim are demolished and damaged, and the devices we use emit poisonous gas that contaminates vast stretches of land, destroying not just the amazing species but also the vegetation. It’s not subtle to say that humanity is small-minded, self-centered, and foolish. What’s even more obvious is that humanity is completely unable to stop itself from repeating the same faults that forced them to leave Earth in the first place. Only the unspoiled areas of the planet flourish, and only the native Na’vi people have the ability to communicate spiritually with their surroundings. As a recently freed Na’vi Sarentu who was nurtured in captivity and cryogenically frozen for more than ten years, your task is to eradicate all evidence of the Big Bad RDA and Man’s conceit from this planet.

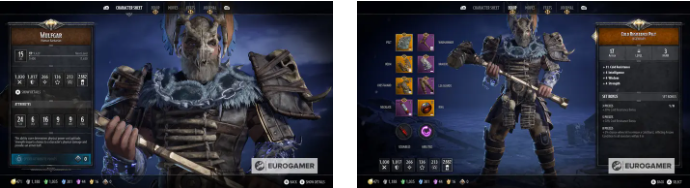

There are a lot of things that will seem similar to those who are acquainted with Ubisoft’s open-world approach, which may come as no surprise. It’s no secret that I’ve always had a little obsession with it; the quest for upgrades, collectibles, and idle exploring quietly satisfy my need for it. When Avatar allows you to explore its world at your own pace and on your own schedule, it is never better.

A lot of content has been reused from Ubisoft’s preexisting plan. As you progress through the massive virtual playground, you’ll uncover it one mission at a time, shooting, stealthing, crafting, and learning how to get along with the wildlife—or not, depending on your perspective—by demolishing outposts and performing errands for the locals.

Nevertheless, Ubisoft has updated the recipe with a few new features, such as a light-touch survival meter, so you shouldn’t start playing until you’ve completed six ready meals. To move you around more quickly, there’s also an enhanced traversal mechanism. At least, that’s the premise.

The idea is that you’re supposed to move through the enormous, tangled tree canopy as if you’re a part of the forest, hopping, bouncing, and extending as you go from branch to branch and tree to tree in a blue blur. Actually, however, I felt more like I was “falling with style” (like in Buzz Lightyear’s “Falling with Style”) than I was truly communing with the jungle. Yes, this might just be a personal preference rather than a game-related issue (I’ve only played for about 25 hours, but Avatar is huge, so I feel like I haven’t even touched the surface in terms of skills unlocked), but I had assumed by now that I would at the very least feel more at ease moving around the environment. You’ll be able to soar over the plains and going from point A to point B will seem a bit less like a chore until you acquire your enormous flying dragon-dog friend later on. But don’t let it deter you from at least attempting to master the parkour elements—that won’t happen for many hours, my buddy.

It’s also… loud. both visually and aurally. Although the rich, alien vegetation of Pandora is really astounding and a true pleasure to explore, it may be difficult to concentrate on what is directly in front of you due to the large, heavy leaves, swinging branches, and rippling undergrowth. If Avatar didn’t imitate the investigative gameplay of Assassin’s Creed, where you had to look about you to piece together evidence and figure out what precisely occurred before you showed there, then this wouldn’t be such a horrible thing. Even then, it wouldn’t be all that horrible if such investigation scenes were limited mostly to the areas of Pandora where humanity has wreaked havoc; the drab, murky backgrounds would make things much simpler. But since Pandora is alive and constantly moving about you, and because certain investigations need you to identify microscopic things or clues, it may result for some really stressful scenes.

Furthermore, I’m certain that Pandora’s vibrant environment is the reason I always get lost. Yes, it’s no secret that I have no sense of direction and can get lost in a barren room, but Avatar’s constantly shifting landscape and infinitely undulating universe make it difficult to remember where you’ve been, much alone where you’re heading. Even with your superpowerful Na’vi senses working overtime, you can’t locate them for love or money, even if they’re eleven billion feet tall and a vivid crimson blue color. Occasionally, you’ll hear a voice, maybe that of a local healer or forager.

The same is true of the internal habitats, such as Hometree and Resistance HQ, which are enormous, chaotic labyrinths of rooms, branching paths, and various levels, but neither a wayfinder nor a mini-map can assist you in finding specific locations like the crafting table, your stash, or the Community Basket, where you can donate scavenged goods to win over the locals. All you can do is keep poking your Na’vi sense until something somewhat recognizable comes into focus.

The fighting also seems like a step backward rather than the forward motion I had anticipated. A stealthy bow and a spray-it-and-pray-it assault rifle will give you two combat styles right away. However, even though I used to enjoy stealthing in old Ubisoft games – oh, the hours I wasted, sitting atop a cliff and silently eliminating opponents until no one was left to sound the alarm – there never seems to be the mountainous topography I long for near RDA outposts.

As a result, no matter how hard I try to stay on the QT, I always feel like I’m going the High Chaos road, because once your enemies find out you exist, they never stop, not even if you hide. This is especially troublesome if you run out of conventional metal-and-gunpowder ammunition because, well, guess what? You’ll always be running out of ammunition. Occasionally, you may lack the leisure or time to meticulously align your bow with a headshot. Especially not with five deadly mechs aimed on you.

However, it’s still early. It’s possible that I’m just a mission away from finding the ideal weapon, but since my map is still incredibly hazy, I haven’t reached level ten, and a problem that might or might not be a bug has prevented me from moving forward, I can’t give Avatar: Frontiers of Pandora a rating just yet. And that’s OK with me, just between us. I’m not willing to forego the side missions. I want to take my time. I’ll concentrate on that and get back to you as soon as Pandora has showed me all it has to offer since the trip between the missions is what makes these games so magical, not the missions themselves. I’m eager.

Ubisoft received a copy of Avatar: Frontiers of Pandora for review.