The arcology backdrop of The Ascent is fantastic, if somewhat unoriginal; too bad there’s nothing to do except shoot and grind.

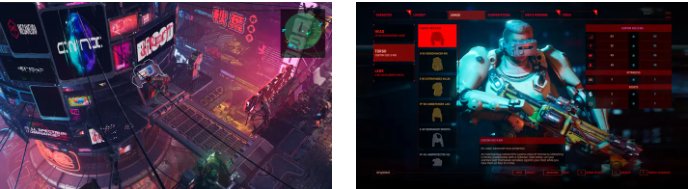

The Ascent is humming. One of the most vibrant cyberpunk environments I’ve ever seen is its layered alien megacity, which is always bustling with people and machinery whether you’re killing mutants in the sewers or looking out of a boardroom window. It is true that the film is full of cliches and references to classic works such as Blade Runner’s reflective synth score and fluorescent umbrella handles, William Gibson’s “high tech, low life” phrase that flickers on displays throughout the film like a sorcerer’s incantation, holostrippers from various seedy sci-fi saloons, and an Oriental faction that worships honor and wields katanas. This isn’t your typical norm-busting, transgressive punk fiction; in fact, Ruiner, its nearest relative, is a complete surprise. However, The Ascent’s environment almost makes up for its lack of inventiveness and bite with its massive scope and toymaker’s meticulous attention to detail.

Consider the stores. I want to live in them, but I think that’s just the lockdown talking. You have never seen such stores, really! Wireframe, spinning weaponry encircled the armor. 24 hour shops and soylent-green pharmacies exude the fading atmosphere of an imminent hangover. Robotic philosophers manning fortified gaps in the wall. Outdoor marketplaces including textiles, metal clanking, and steam. Every shop is a little, fragile treasure trove, with a cover that lifts off as soon as you enter and goods that are arranged in a nice arrangement like chips on a circuit board. What about that lighting, by the way? Filthy, hazy, fluctuating, overpowering. The main districts of the arcology are a war royale of Hangul writing and billboards, a jumble of displays and reflections filtered through pollution, delivery drones’ winding trajectories and the shuffling corpses of hundreds of exhausted non-playable characters. Even with the breadcrumb trail the HUD provides, it’s simple to get lost, and I don’t mind at all. The city of The Ascent is a haven for internet explorers. It begs to be left alone.

Here, the heightened diagonal perspective works wonders, creating a world of corners that divides the scene into luscious, striking compositions of various colors and textures. The way floor plans and architectural features align with, or defy, the axes of shooting and exploration proposed by the quasi-isometric perspective, is visually fascinating on a primal level. The idea behind the vertical city is a little deceptive: the world is really made up of flat surfaces connected by loading transitions; it doesn’t even recognize the necessity for a jump button. However, the game skillfully creates the sense of enormous depth. Hundreds of meters below, chance openings and reinforced glass floors provide dizzying vistas of hovercars passing through chaotic tunnels of industries and tenements. While there are certain depths that can be reached by elevator or floating platform (think Abe’s Oddysee with its fore-to-background movements), a great deal of work has gone into making unreachable areas come to life. Just above the navigable level, you’ll see balconies packed with revelers and showers of sparks from droids mending the sides of walkways.

What then do you do in this astounding environment—the product, you would think, of twelve developers’ labor? After gushing over kiosks for three paragraphs, let me try to sum everything up in one sentence: go to the next objective by following the HUD’s instructions to a quest marker, circle-strafe to avoid attacks until everyone is dead, use your level-up points, and maybe stop along the way to upgrade or sell off some items if you come across a merchant. That’s how the game works. Well, not exactly. Hacking exists as well, but it’s mostly a glorified backtracking incentive and gating feature, with stronger cyberdecks enabling you to bypass forcefields that divide city districts and break encrypted treasure boxes.

What a terrible waste of a place. Furthermore, the tale is a waste. Characters range from an apoplectic criminal lord to a cold mercenary captain – Hitman’s Diana Burnwood after a trip to the ripperdoc. The prose is standard cyberpunk stuff, with overcompensatory c0rpoSlang and edgy self-interest. These gregarious individuals are more like grab-bags of attitudes taken from TV clichés than true personalities. However, the story’s idea is very fascinating. The majority of people living in The Ascent are indents, interplanetary explorers who now have a lifetime commitment to repaying their trip expenses. The company in charge of the arcology has inexplicably filed for bankruptcy at the start of the game, leaving everyone’s contracts in limbo and their ownership of utilities like the power generators and AIs at the bottom of the earth in jeopardy.

It’s a breath of fresh air in a town that has functioned for decades as an exaggerated debtor’s jail; imagine quiet chats amongst exhausted laborers who used to dream of creating paradise in the streets. There’s no hope for improvement since everyone knows right away that a large company will ultimately take over. The majority would really prefer it that way: “business as usual” sounds good when the plumbing breaks, much alone when gangs start to gain ground against the increasingly underfunded corporate police. However, this unsettling beginning, the toppling of a civilization built on punishing debt, seems like a solid basis for a narrative about the workings of a dangerously realistic capitalist dystopia. It’s unfortunate that your only function in the game is that of a self-aware bludgeoning tool, a melancholic, wordless grunt who is only happy to carry out the commands of those who are in a position to issue them.

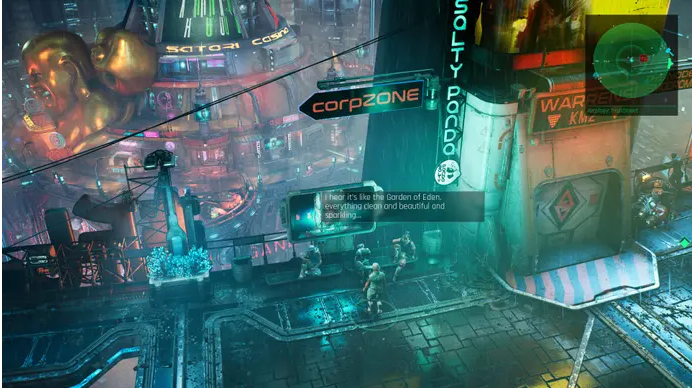

One may argue that The Ascent’s shooting and leveling, in all its brutal simplicity, serves as a reliable and inconspicuous delivery mechanism for the subtleties of the city. But this rapidly becomes tedious since the RPG elements are dull and involve backtracking, making exploring the city a chore. The shooting is also not that impressive. As a shooter, The Ascent does feature some unique concepts: it balances Diablo-esque bullet-hell evasion with Gears-style tactical fighting. With a laser pointer and customizable autoaim, it handles similarly to a twin-stick shmup. However, you may shoot above cover by crouching down and holding down the left trigger. By default, you fire from the hip, but if you want to increase the likelihood of a critical hit at the sacrifice of movement speed, you may also bring your weapon to your shoulder by holding down the left trigger.

Creating an exciting contrast between sliding about blasting as in Geometry Wars and carefully settling an encounter like in Ghost Recon seems to be the objective, I believe. But without co-op partners, at least, it doesn’t really come together. You seldom have the luxury of getting deep into the game because to the limited sight and the way that goons appear from all directions. It’s easy to lose sight of whether you’re standing or crouching, or if your bullets are tearing through the barrier in front of you, since there’s so much going on in any one moment. Thus, you continue your frantic evasion, kiting the masses around cover patterns and retreating into health drops. At least you don’t have to worry about running out of ammunition since all of the guns—from rocket launchers to energy rifles—have infinite magazines and varying reload times.

I was reminded of pitching a tent after midnight and being eaten alive by mosquitoes by one late-night gaming encounter.

In any case, level differences are more resilient than walls or your dodge-roll: if you complete a few sidequests for each major story beat, you can usually go through everything with a handcannon pointed directly at the enemy, even if you forget to select the most effective attack type (energy-based, ballistic, etc.) for that particular enemy. You may even sulk at narrative missions because, if you don’t mind hearing the same dull mission script over and over again, experience points earned from kills carry over between deaths.

The irksome timed wave-defence missions that conclude several narrative missions are the largest deviations to the Rule of Grind. Later on, adversaries start showing up in groups of ten or more, turning The Ascent into a veritable butcher factory. In a particular late-game encounter, you must successively activate four hold-the-button terminals to repel mutants. The experience reminded me of setting up a tent after midnight and getting eaten alive by mosquitoes. While you may use robot buddies to inflict some harm, having a human opponent at your side is still preferable. Although The Ascent is primarily a solitary game, these intense sequences serve as a subliminal push towards the multiplayer options, which include public or invite-only online play and—spoiler alert—a local cooperative mode that I’m eager to test out on console. Unfortunately, over my 20 hours with the game, I was unable to arrange any team-ups due to lockdown limitations and pre-launch review circumstances.

Without body changes, the plot wouldn’t be cyberpunk, but they are basically standard action-RPG powers wrapped in a Deus Ex package. Augs include detachable turrets, AOE hits, the customary Iron-Man chest beam, and support abilities that drain health or put enemies in stasis. They work well with the run-and-gun, often changing the course of a fight, but they’re quite boring and don’t add anything to the mix. There is some strategic tension between enhancing attributes or abilities when your character’s stats (such as resistance to stagger, health bar, and odds of critical hit) are upgraded; however, there aren’t many battlefield combos beyond standard RPG alchemy, like priming opponents to explode when they die. The opponent concept is similarly standard, experimenting with debuffing hackers and static defenses but largely relying on riflemen to pin you down and kamikaze guys to flush you out. Bosses have larger health bars and more audible AOE abilities. You will scamper away from them until they pass out from sheer frustration, much like Monty Python’s reluctant gladiator.

Then there are the issues with technology. My PC is a little unstable, so I’m hesitant to hit the trigger too hard, but if my hardware can handle a game at med-high settings, it should be able to run it without randomly crashing all the time, having characters get stuck on the geometry, taking a long time to load entire sections of the floorplane, or, worst of all, having special abilities malfunction during combat. There was a moment when the sound of power generators was disrupted by hover traffic, creating a noise that resembled a lightsaber fight inside a washing machine. After about an hour, the fire button quit functioning. Fortunately, these problems also affect opponents: I will never forget how appreciative I was towards the end when an assaulting posse suddenly put down their weapons and sat there, staring at me, as if they were just as weary of the battle as I was.

The longer you play, rising to the pinnacle of the arcology and overthrowing its titans, the less captivating this amazing metropolis becomes. Through quests, you travel between distant NPCs, with random floor defenses by thugs interfering with your progress every few seconds. There are quick ways to get about, such as free metro stations and aerial taxis you can call in for a little cost, but you can only get between arcology layers via the central elevators, which means more walking and more dull combat possibilities. The worst part is that most dungeons are located near maintenance districts, ports, plants, and factories; if you get to a monster you’re not leveled for and need to level up your gear, you’ll have to go all the way back to the hub.

Nevertheless, it’s a pleasure to be back in the larger cities after these taxing encounters, searching for new sights and sounds, new ways for the setting to express itself, rather than so much for sidequests. Aliens doing out outside in gyms. People kicking vending machines or sweeping up, the favorite activity of the RPG onlooker. Club patrons hurling shapes (a shoot-out evoking the opening sequence of Blade) and inebriated individuals staggering back towards the bar. Researchers arguing in front of shiny centrifuges. The game’s goal and combat aspects quickly blend into a blur as all these moving pieces soak into memory.

In contrast, despite your growing strength and polished look, it seems that no one remembers you. When a round is released, pedestrians flee, yet moments later, nothing seems to have occurred. Gangs that reappear seem blind to your increasing murderous history. They’ll whimper, a level 4 to your 20, waggling their dukes like Scrappy Doo facing the Terminator, “Want to meet your dead relatives?” And there’s the possibility of consequences for taking the lives of people; the mercenary captain, who happens to be a wintry one, will tell you everything about it over the radio. However, they never appear in the game—at least, not for me. These admonitions start to seem more like Call of Duty’s hypocritical slaps on the wrist for friendly fire, rather than references to a morality system a la Fallout.

News reports during elevator rides do monitor your larger-scale devastations, and you will unavoidably decide the general direction of the city throughout the story. However, the people you meet and the places you visit never really represent your position, reputation, or preferences. And why would it matter to them? You are just another gangster trying to take over the world and work your way up to that much desired boardroom view, after all. Again to paraphrase Gibson, “the street finds its own uses for things”. I doubt the player will find much use for the streets in The Ascent.