I keep playing games like these to get back into rhythm. Action games have always had some element of rhythm; excellent fighting is like dancing, while poor combat is a bit out of step. It’s all in the one, two, dodge, the half a beat between the third and the leap, the small passive mental clock ticking over from that boss’s second smash to the third.

The same is true in Death’s Door, an exquisitely lovely Zelda-like story about the unchanging pulse of time and the rhythm of life and death. However, there appears to be an additional, elusive element that gives it an edge. Death’s Door has a flavor, or maybe more accurately, an experience rather than a flavor. Tasteful. What is dance’s umami?

Titan Souls, developed by Acid Nerve, was their most recent game, released back in 2015. One of those games that is all about simplicity is Titan Souls: you start with one arrow, you die in one hit, you have a world to explore and a good number of enemies to take down, and then you’re off and running. Its brilliance is the kind of classic independent creative cleverness, where you merely develop outwards from an arbitrary starting point to keep things focused and the notion pure. This backdrop is crucial because, if you expand from Titan Souls, you’ll eventually reach Death’s Door, a game that offers both lots of freedom and constraint. As a studio, Acid Nerve comes across as having a clear plan and a clear trajectory, but then as a result of that so do its games. Bosses, combat, a mysterious overworld, and some mildly perplexing environments – the entirety of the first is the foundation of the next.

The lucidity of Death Door is crucial; it finds the right balance between the fight and the world’s seeming sparsity, as well as the complexities that are really hidden away. The scenario involves you as a crow working as a reaper for a large group of other, more bureaucratic crows in an afterlife civil service. It’s your usual duty to go out and harvest the souls of the deceased; but, you must hit the person with your sword first if they have managed to elude death and live longer than they should.

This seems complex enough, yet it isn’t because of a persistent, ethereal appeal. Death’s Door is quite gloomy and often pretty depressing. A buddy of his who works as a gravedigger and yearns for death’s serenity but is unable to pass away will deliver the eulogies for fallen enemies. Here, resisting death corrupts souls, thus another buddy wishes for peace for his rebellious grandma, who is unable of bearing any more losses. Its pastel, earthy worlds are half-alive, half-empty, full of cobwebs, fallen leaves, sunken ruins, and forests. The entire thing feels like earthenware, actually, but maybe a piece that’s still an hour or two from setting, a world that seems capable of both being squished like clay and smashed like a vase. Characters living in a world always in fall, and stuck between life and death.

Yet it’s also humorous. Quite humorous, in fact, in that genuine comic kind of manner, the comedy of surprise, like a sign that remains readable even after you unintentionally chop off half of it with a sword, but just the lower half of the text—and the upper half, too, if you read the section that is now on the ground. The characters are strange. For starters, there are crows that seem bookish, but they are paired with an octopus that disguises itself as a man by using a cadaver, a man with a pot for a head, magical urns, and gobs of slime. All of this is animated with exquisite care, as evidenced by the little crow that occasionally tilts its head, the occasional slumped shoulder, and the pitter-patter of its feet on wood or stone. Human-centered animation with weird characters who have an odd sense of life.

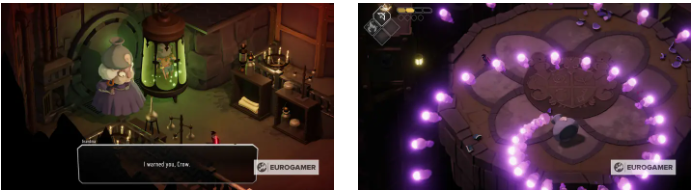

Everything sounds so soft! However, it’s not, so: war. Death’s Door presents a nice challenge, meaning that although it might be mechanically hard at times, it is always achievable and never harsh. Your primary goal is to defeat the three main bosses, who are located deep within their own worlds and can be accessed from the main hub one. You can also short-hop between the bosses by using doors that unlock as you go, which allows you to return to the reaper bureau’s hub and hop through additional doors to go elsewhere. Each one opens up additional abilities beyond using a sword, such as a bow or throwable explosives (hello, Zelda!). These abilities also, in true metroidvania fashion, open up new routes and regions of the game.

Because you have a bit more health and attack options, the bosses themselves are a pleasure, able to expand on the very creative confrontations from Titan Souls by introducing additional levels and rounds of growth. Many of them will remain in my memory as some of the most memorable boss fights I’ve ever played, including that amazing mobile battle-chateau you may have seen in trailers but also plenty more. They all have that unique quality that makes combat feel like a live-action puzzle as much as a mechanical test. The fighting itself becomes increasingly complex as you progress through the levels, building from a tight but somewhat simplistic beginning to a crazy, captivating, explosive finale featuring mini-bosses, grunts, and battable projectiles at the end (you can actually unlock enhanced versions of the skills, which add another layer of subtlety and empowerment to combat, but I won’t spoil things by telling you how).

“What a beautifully concise, measured, exacting, deliberate thing Death’s Door is…”

The atmosphere, which is once again rife with secrets, is the opposite of this. There are secret passageways, cloaked steps, taunting, inaccessible switches, openings in hedges, and oddly crumbling-looking walls everywhere. All of them lead to positive places, such as helpful upgrade cash or really fascinating—and sometimes useful—collectibles, as well as hidden improvements to health, stamina, and skills. Because traversal is tied to talents, it’s always quick, and because of the world’s lovely melancholy, it’s always enigmatic, alluring, and never difficult to go back.

The magic lies in that mix. Even if it’s terrible to constantly bringing up the two Miyazakis, they are everywhere in games, subtle references to them in the hands-off, invisible coaching through struggle (Hidetaka) and the plinky plonk keystrokes of melancholy pianos and landscapes in sorrowful transition (Hayao). Moreover, it is blatantly referenced to crotchety old granny witches in their magical castles with mechanical guts and sharp-toothed chests that devour you up, which makes me feel much better about the allusion. And the little man wielding the large sword.

But what a duo to use as a model. What an amazing foundation Acid Nerve has to work from—not just their own outstanding debut, but also Zelda, a 16-bit adventure, to this, all without a single piece of baggage acquired along the way. Death’s Door is such a wonderfully written, calculated, meticulous, thoughtful work. How kind, witty, and depressing. How rich in texture. And such joy! It is just not to be missed.