The sequel to the classic DS game, NEO: The World Ends With You, is a charming addition to the franchise

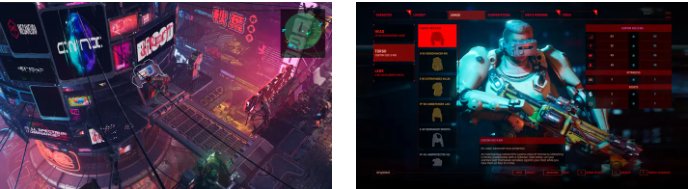

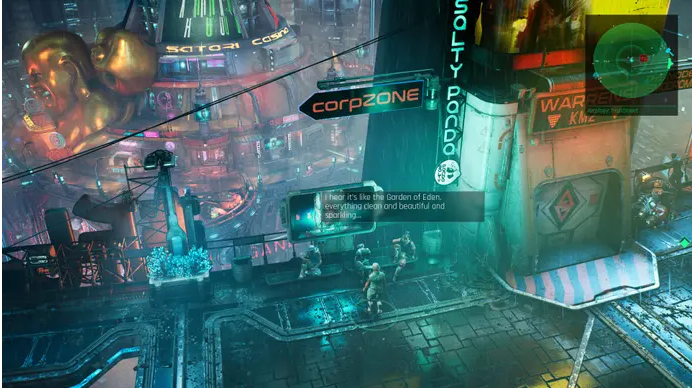

Tokyo is the world’s biggest metropolis, and it also seemed to be the busiest during my first visits. The busiest thing about Shibuya, in my opinion, is how much visual information is always present: signs, screens, calligraphy, graffiti, and city mascots. It’s maximalist and overpowering, and a total joy to see. I’ve always come and gone, but I’m sure it gets better the longer you stay. I kind of don’t want things to get better. And NEO: The World Ends With You does a fantastic job of depicting this type of event.

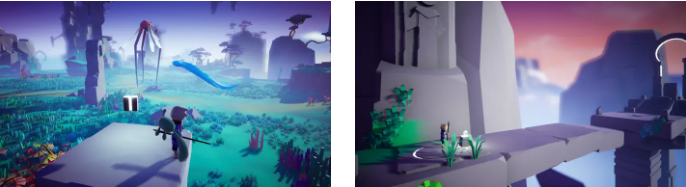

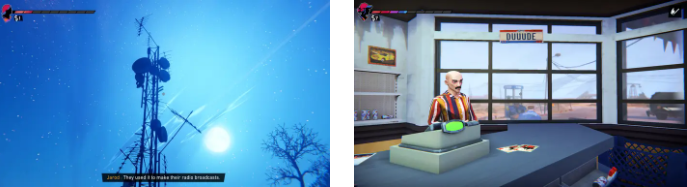

Neo is an RPG that is situated in the Shibuya neighborhood of Tokyo and is the follow-up to a beautiful DS oddity. It has a sweeping view of the city’s skyscrapers, crooked retail lanes, highway underpasses, and much more, all from the renowned Scramble Crossing. Tokyo, a certain type of Tokyo; a huge, diverse metropolis, caught in all its chaotic beauty. Jet Set Radio plied similar emotional ground here, too: a world of youth, fashion, brands, shopping, friendship, phone messages, and pop culture allusions. At times, you may recognize the pavement or the cant of a renowned structure.

However, that assault of maximalist visuals! In my opinion, you experience it twice: first while navigating the streets where the plot and objectives of the game take place, and again during battles, which is were the game’s burning spirit resides. Where to search! In the initial DS game, you had to alternate between the top and bottom screens to control various combatants using different input techniques (button taps on one, stylus swipes on the other). You had to take on a variety of fauna, including hawks, frogs, and other creatures with tattoos. Neo does this quite a bit. Many of the adversaries are recognizable, especially those up front, and many of the attacks you level up and collect—which are given as pin badges—also appear from the previous game. However, not two displays. Absent a stylus. How should one proceed? Where should I search?

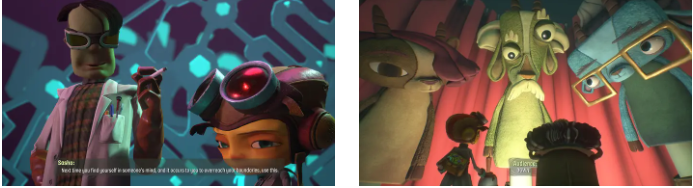

Neo is still a fantastically chaotic game, even if it would seem a little strange to discuss the plot and other aspects before discussing the battle system. Now let’s get started. In Neo, you may command a group of warriors at once during battle, each of whom being powered by a unique badge. By the time you have four individuals to manage, you will have a triangle person, a square guy, and a few bumpers or triggers since badges have separate inputs. I like to start with the triangle, which is usually composed of sharp, repeated taps that resemble blows or maybe slashes from a sparkling blade. Square supports them with lightning, or so to speak, magical arrows. After that, I may press the bumpers and triggers to heal, or to summon an iceberg that will pierce the earth; the larger the berg, the longer I have to charge the button.

You already have too much on your mind when you include in dodging and the fact that the spiky menageries you battle against like to attack in mix-and-match groups. Neo, however, is just getting started. A Groove meter appears at the top of the screen and increases as you launch strikes. The way it works is that you use one move to attack enemies until a combo timer appears. Then, you may switch to a new move and continue the combination until another combo meter appears, alerting you to switch again. You may perform a special maneuver when the Groove meter full, and while that happens—fireballs, ice shards, wandering Top of the Pops lightning strikes—you might be replenishing your meter. It need not come to an end.

You’re balancing the cooldowns for each badge and its attack, and here is when it becomes incredibly important to know where to look. As a result, you are getting closer to a cooldown as you poke about with the triangle. Before breaking the chain, is it possible to timing it so that you move to a new party member and launch a separate attack? Can you continue to switch in order to avoid the intervals of recharge? And can you do so while monitoring what your groove meter is doing, incoming strikes, and which party member has been rendered paralyzed by a jellyfish?

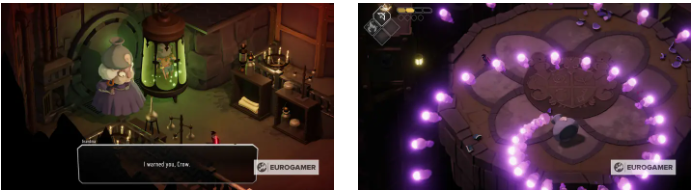

I adore the fighting, which only becomes more joyfully complicated as the narrative moves further. Furthermore, it looks stunning right away. Thick black lines, anime heroes, trendy hairstyles, and exquisitely detailed youth clothing are all hallmarks of Neo’s visual excess art style. Your attacks—massive laser blasts, flame-spewing torrents, and sparkling magic—inevitably blend in. And the adversaries! One shark from the early stages of the game that I really like is the one that loves to swim under the pavement before erupting. There are bosses, the finest of whom I cannot discuss, but one of them had me laughing so hard I was crying, and jellyfish, which usually indicate that you will be busy, come in pairs. Prioritizing targets is only one of many factors you have to consider at the conclusion of the first act of the game. Enemies also need targeted attacks from certain angles. Yes, and the opposing teams are there.

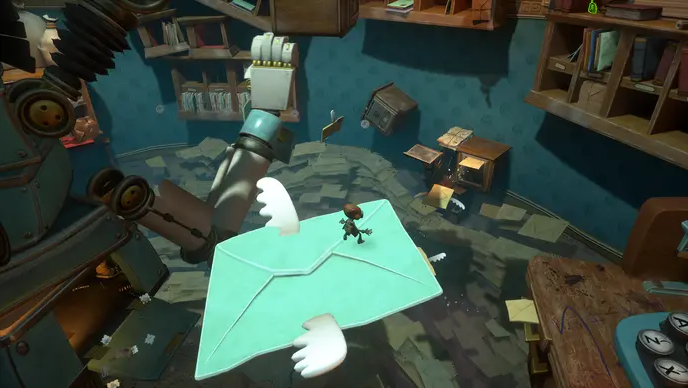

The tale enters at this point. You and your group of pals are essentially thrust into a metaphysical reality TV game show, much like in the previous game. You are stranded on an interdimensional island made out of Shibuya landmarks, and a group of Reapers—hipster game experts—are in charge of dividing your life into days and eventually weeks as you compete against other teams to win. Every day brings a new assignment, which might be a set of riddles, a mysterious chore to do, or a territorial capture game in which you race across the globe while facing monsters and other teams. One side emerges victorious at the conclusion of the week, but the losing team really suffers a defeat.

All this amounts to is a happy pretext to throw one wonderfully bizarre caricature against another. In the soap opera narrative that rapidly develops around your efforts to comprehend the Reapers’ game and survive, other teams are frequent invaders. I really like the cruel girl who thinks life is just a game of Reversi and the team that is crazy about rivers—but what type of rivers? The narrative does a great job of putting you at odds with other teams while evoking a sense of empathy from you as they conspire and counterplot against you in a desperate attempt to avoid finishing last by the end of the week. Even though it’s well staged, your phone never stops pinging with information on other teams’ accomplishments. It gives you the impression that the contemporary world is always changing around you.

It goes beyond the teams. Often, a job will have you traveling about Shibuya and making changes to the lives of people who aren’t able to see you or communicate with you while you’re in the Reapers’ game. Some people suffer from negative feelings, which you dutifully fight for them by vanquishing the demons that feed on their souls. Some people need a moral nudge or a reminder. You may help them by entering their heads and creating simple concepts for them, one word at a time, or by completing puzzles to help them remember things. The game is pleasant and humorous most of the time, but there are moments—one in particular—when it really struggles with the consequences of this stuff. Still, for gamers like me, it provides a nice window into the concerns of a far-off metropolis.

Tokyo! If fighting is one of Neo’s greatest strengths, the city is another; exploring Shibuya and its surroundings is a delight, since they are divided into tidy tiny areas that blend in with while maintaining their own personalities. The game has a strong tourist appeal, and it’s lovely just to gaze around. However, there are also pedestrians, whose thoughts you may read by entering a another world where you can chain creatures to orchestrate some epic fights. There are stores where you can purchase equipment to raise your stats (you can level up the stores to obtain better items) and eateries where you can permanently raise your stats but there are cooldowns if you overeat. Every one of these places has an own personality and offers unique products. I could eat Scramble Crossing’s appetizing-looking cheeseburgers for eternity, and the other day I wasted twenty minutes trying to recall the location of a certain bookstore. I simply wanted to look around; I didn’t even need a book.

Considering how compact its map is, Neo is remarkably large. Of course, there are all those pins with their various attacks and synergies to locate and level up. There are the opposing teams to battle and gradually acquire insight from. When difficulty spikes occur, there’s a good deal of grinding involved. In addition, there are all the ingenious business devices like time travel and therapeutic dives that are used to turn fighting, puzzle solving, and traveling around into distinct jobs. Yes, Neo might be a little repetitious at times, but in my opinion, its two trumps come to the rescue. One thing that never got old to me was going backwards through Shibuya and taking in all the stores, people, and landmarks. It also created many opportunities for puzzles that required me to examine the urban environment closely, with one middle-act example being especially entertaining. Furthermore, those bouts are simply so much fun—they sometimes resemble rhythm-action as you alternate between the attacks of different party members, maintaining the beat and listening to the uplifting support of each member of your team throughout. This hit-pause is nothing short of amazing. With every triumph, you chomp magnificently.

Everything might seem fresh in a situation like this. When an array of attainable benefits is disguised as a network of your developing social connections, complete with nodes that you may access by transferring friend points to acquaintances, it takes on a rather unique vibe. In addition to their ability to develop and unleash powerful strikes, those badges also have a very coveted and collectible appearance. The characters are well-drawn, and everything chatters along with the ping of incoming messages and status updates, even if the narration may be somewhat lengthy at times.

Sometimes I have a pleasant twinge as well. I’ve been to Shibuya myself, once staying at a hotel across from the Scramble Crossing, and every now and then I get this weird familiarity shock. However, more often than not, I get the impression that worlds are peering into one another—the world of Neo passing by the world of Jet Set Radio. Tokyo is so big that I doubt I could ever get to know it, yet video games give you a great perspective of it from many angles. This really is a generous game.